The Money Trail – Analysis

The fundamental question is whether site fees and retrieval reimbursements are being used as proxy payments to circumvent the state and federal laws which make it illegal to buy or sell human body parts. As we examine that issue, it is crucial to remember that for any transfer of aborted baby parts to be legal they must be donated and not sold. By law, the only financial remuneration that is legally allowed is recovery of the actual and reasonable costs associated with the retrieval process.

Our figures show that when AGF’s monthly retrieval costs ($6,656.66) are subtracted from the retrieval income shown in the section above, in February of 1996 AGF billed researchers between $12,093.34 and $18,173.34 more for parts than it paid to acquire them.

In short, AGF appears to have made between $12,000 and $18,000 in baby parts profit from this one abortion clinic in this one month. And remember, that profit amount is based on costs to AGF that we purposely overestimated. An audit based on AGF’s actual expenses would inevitably reveal higher profits than those reflected here.

NOTE: When analyzing the financial data, one problem we encountered was that our site fee documentation was for 1997, while the daily logs were from 1996. However, we felt comfortable assuming that the monthly site fees didn’t change much from one year to the next.

During the time these logs cover, the heaviest traffic day was February 22, 1996. On that day, AGF sold 39 baby parts. According to their price list, AGF would have invoiced the buyers between $3,510 and $5,070 for these parts, again depending on whether they were shipped fresh or frozen.

The Money Trail – Miscellaneous

The tissue logs reveal that one baby is often chopped up and sold to many buyers.

For example, babies taken from donors 113968 and 114189 were both killed late in their second-trimester and cut into nine pieces. By applying AGF’s price list, we see that each baby was sold for between $810 and $1,170 depending on whether their parts were shipped fresh or frozen.

Another interesting financial revelation is seen when the tissue logs are analyzed on a “per-day” basis.

During the time these logs cover, the heaviest traffic day was February 22, 1996. On that day, AGF sold 39 baby parts. According to their price list, AGF would have invoiced the buyers between $3,510 and $5,070 for these parts, again depending on whether they were shipped fresh or frozen.

Even compared to the $6,656.66 amount that we grossly overestimated to be AGF’s monthly operating expenses, AGF recovered between 53% and 76% of their entire month’s overhead from sales generated on this one day. If AGF’s actual monthly expenses were used instead of our exaggerated estimation, it is possible that AGF recovered their entire month’s overhead on this day.

AGF vs. Opening Lines

Since we began releasing information about the trafficking of baby parts, a common perception held by those who viewed this material has been that AGF is more ethical than Opening Lines. While it may be true that AGF is less flamboyant than Opening Lines, it is a mistake to assume that this makes AGF more principled. The issue is whether someone is profiting from the sale of baby parts, not whether they are crass about it.

A good barometer to use in comparing AGF to Opening Lines is pricing.

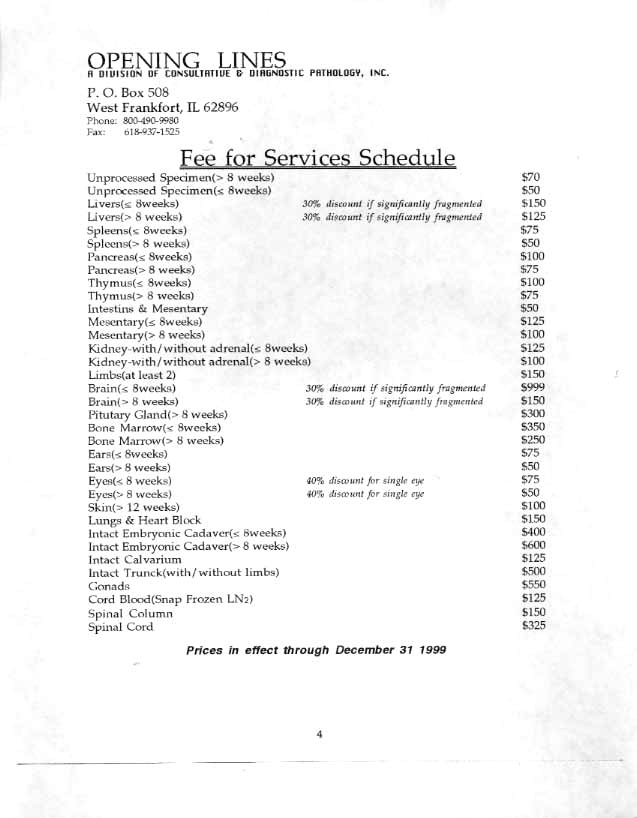

There is certainly no reason that the retrieval costs of one company should exceed the retrieval costs of the other. Bluntly speaking, whatever the actual costs are to pluck the eyes out of a baby or chop off its leg, there is no legitimate reason for it to vary significantly between AGF and Opening Lines. Since the law stipulates that they are not allowed to recover from buyers any more than their actual retrieval costs, and since those costs should be virtually identical for both, it would logically follow that their fees should be virtually identical. As you examine the Opening Lines price list, notice that, unlike AGF’s “per specimen” pricing scheme, Opening Lines bases its prices on the type of body part being ordered.

Earlier in this document, we used AGF’s “Fees for Services” list to price out tissue logs generated at Comp Health during February of 1996. This allowed us to determine how much AGF billed for parts they harvested at Comp Health during that month. The chart below applies Opening Lines prices to those same logs.

| 40 livers > 8 weeks | $5,000.00 |

| 7 livers > 8 weeks | $1,050.00 |

| 10 liver fragments > 8 weeks | $875.00 |

| 1 liver fragment > 8 weeks | $105.00 |

| 7 brains > 8 weeks | $1,050.00 |

| 4 eyes (pair) > 8 weeks | $200.00 |

| 13 eyes (single) > 8 weeks | $390.00 |

| 8 thymuses > 8 weeks | $600.00 |

| 29 limbs | $2,175.00 |

| 14 pancreases > 8 weeks | $1,050.00 |

| 14 lungs > 8 weeks | $2,100.00 |

| 1 kidney > 8 weeks | $100.00 |

| Total: | $14,695.00 |

Recall that when we applied AGF’s price list to these same orders, we found that they sold these baby parts for between $18,750 and $24,830, depending on whether they were shipped fresh or frozen. Opening Lines would have sold the same parts for $14,695.

In other words, AGF charged a minimum of $4,055 more than Opening Lines would have, and possibly as much as $10,135 more. Given the logical assumption that Opening Lines’ operating expenses are roughly the same as AGF’s ($6,656.66 per month), Opening Lines would have cleared $8,038.34 profit from the sale of these baby parts. And while that would represent an astonishing 120% return on investment in just one month, it is still between $4,000 and $10,000 less profit than AGF would have made on those same parts.

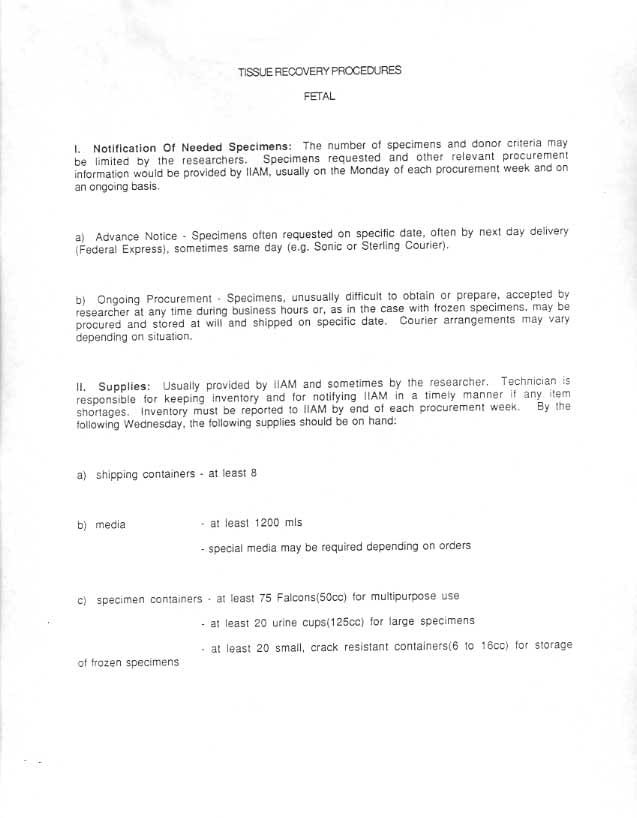

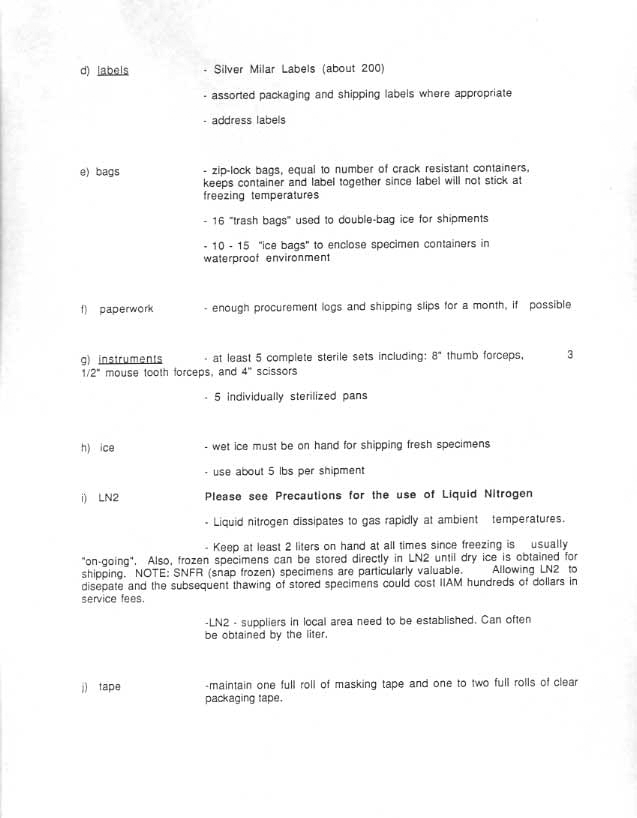

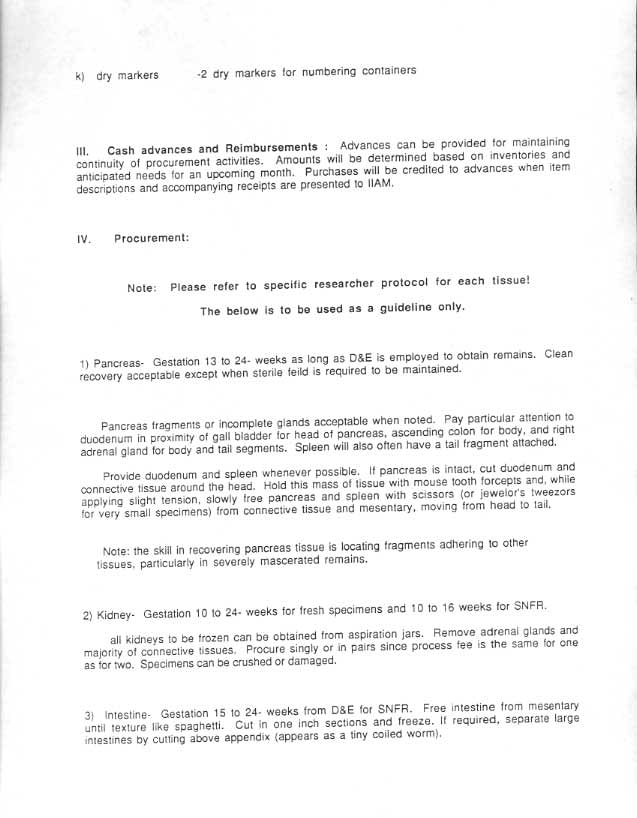

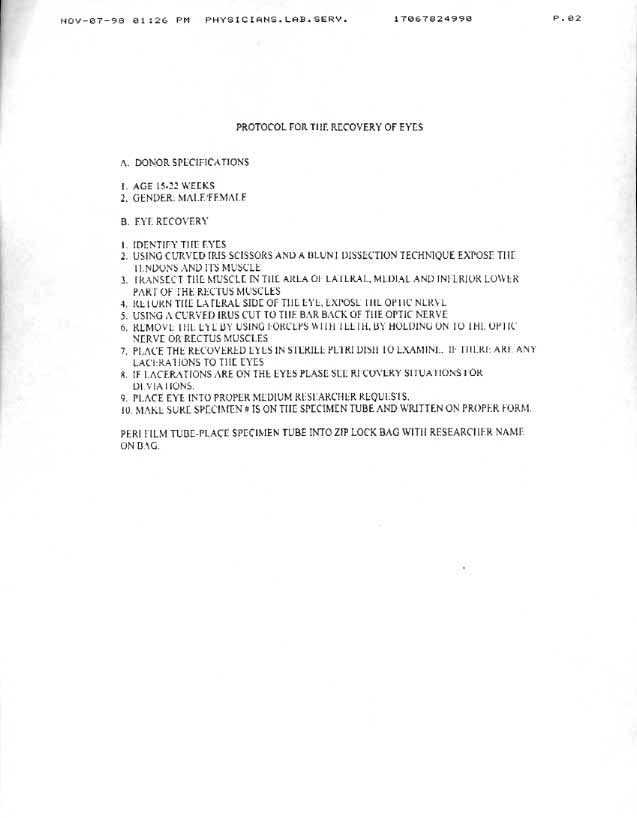

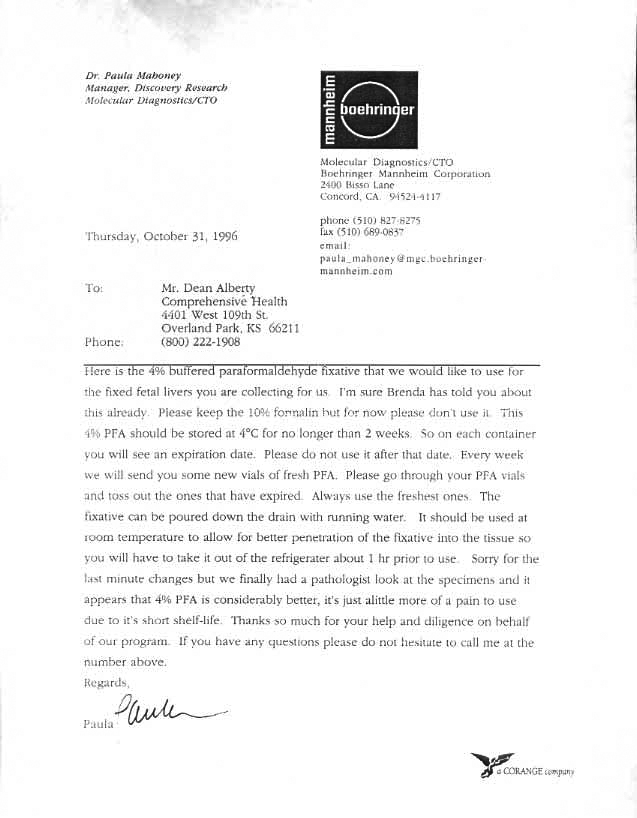

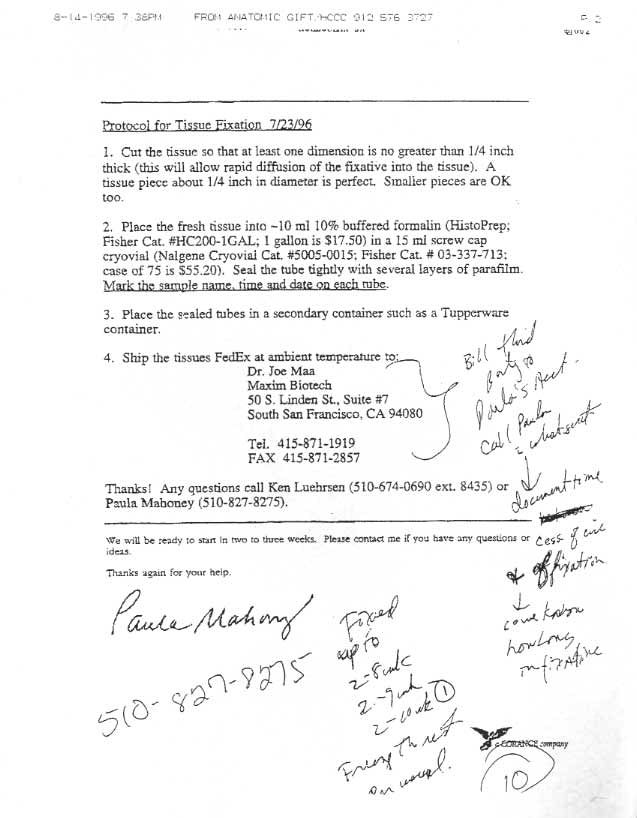

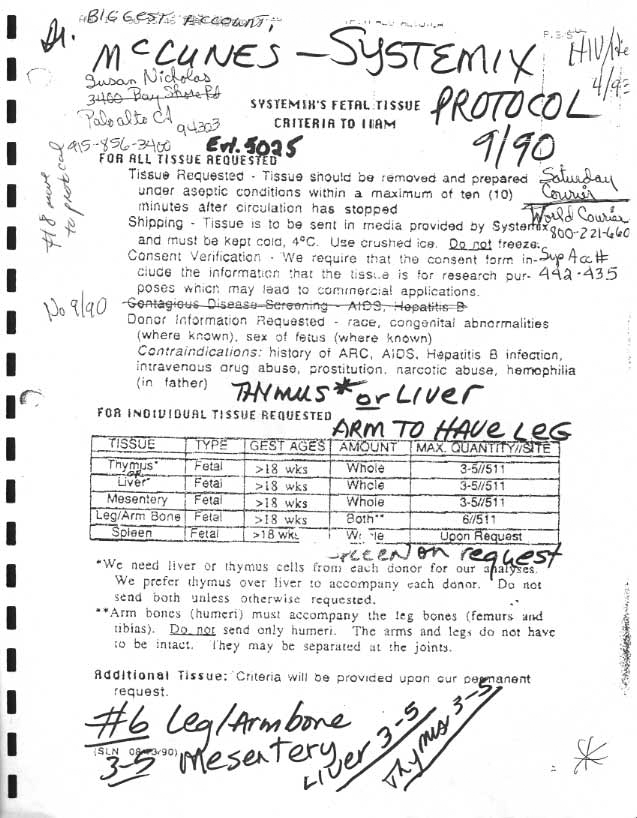

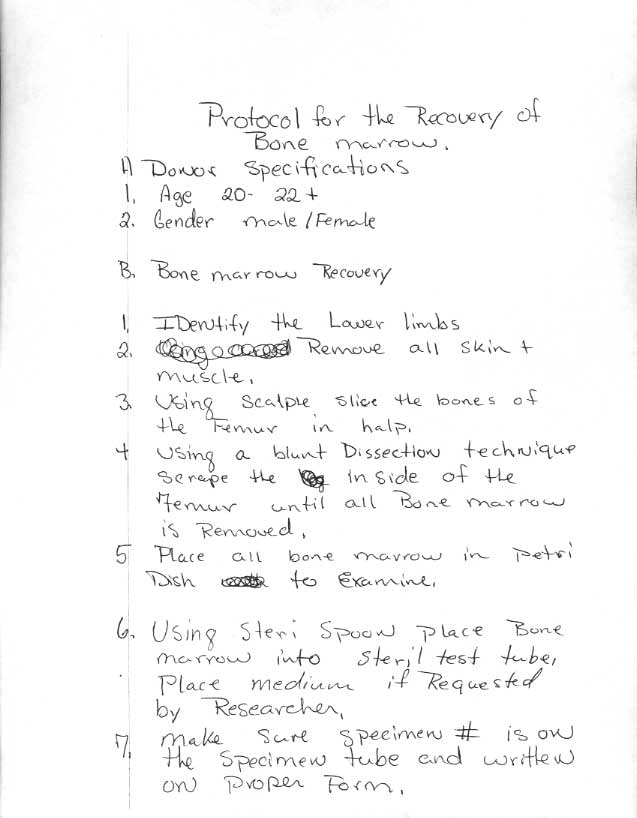

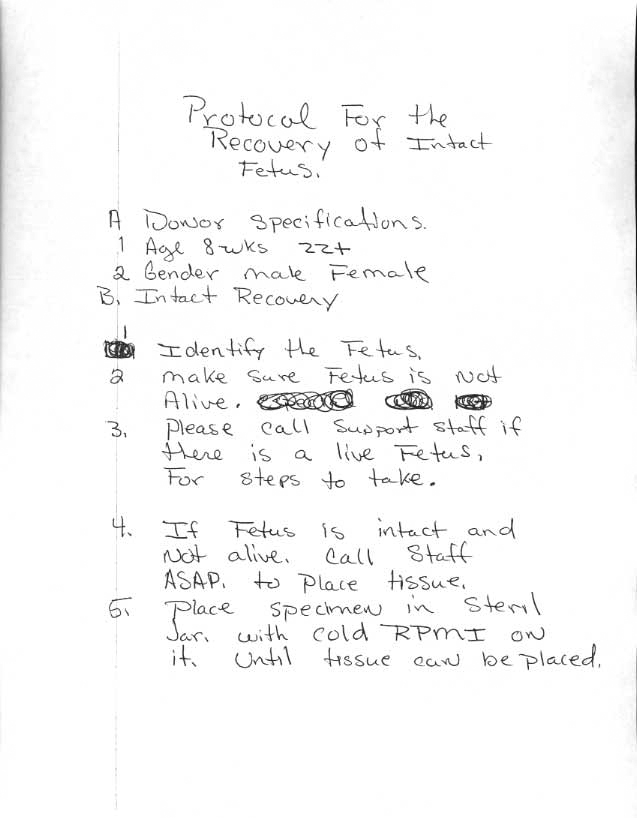

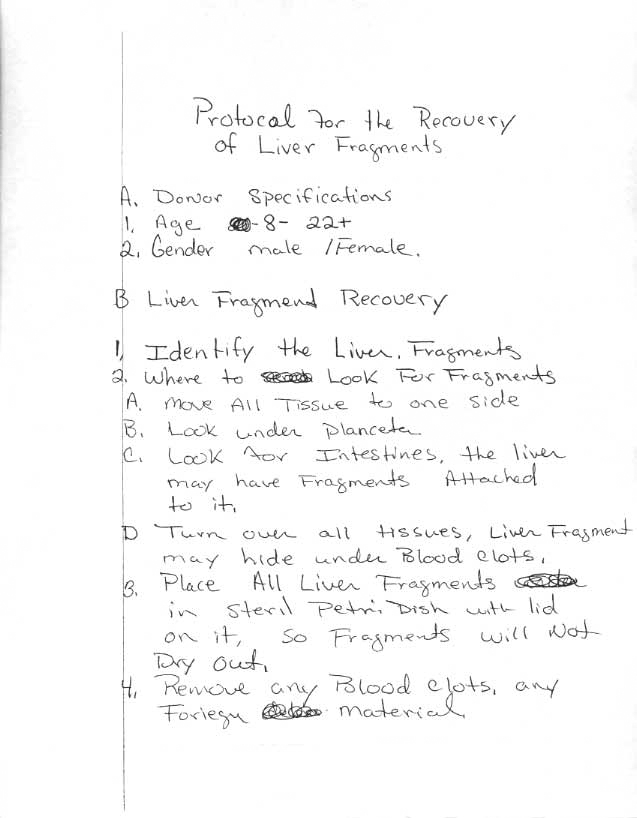

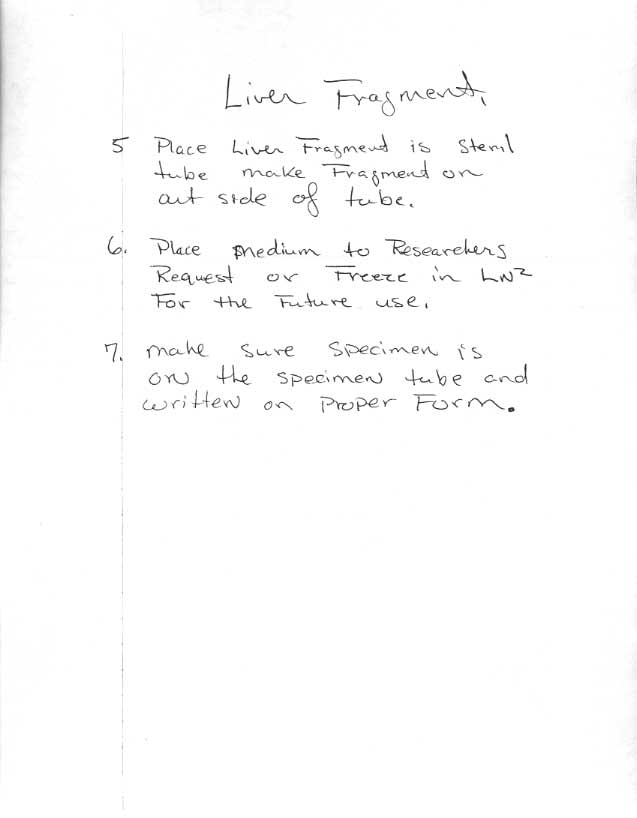

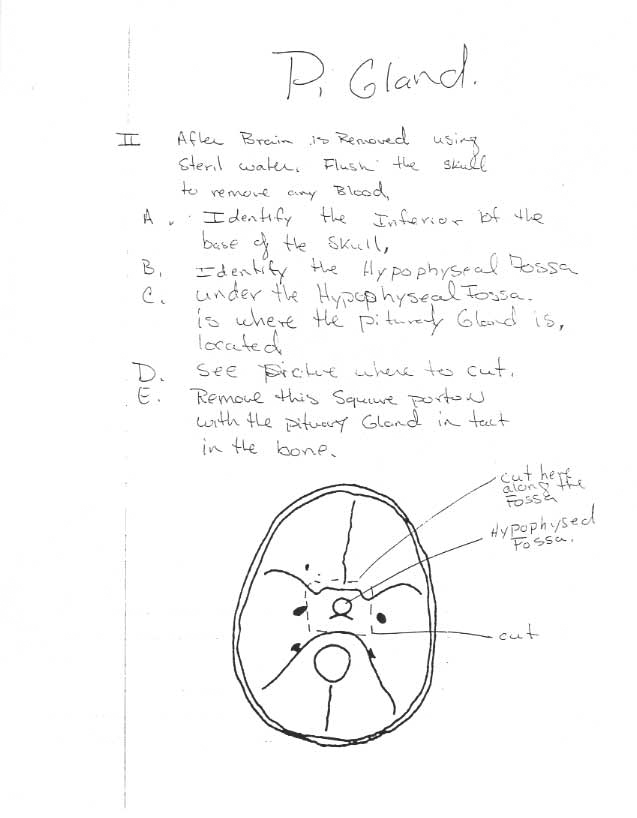

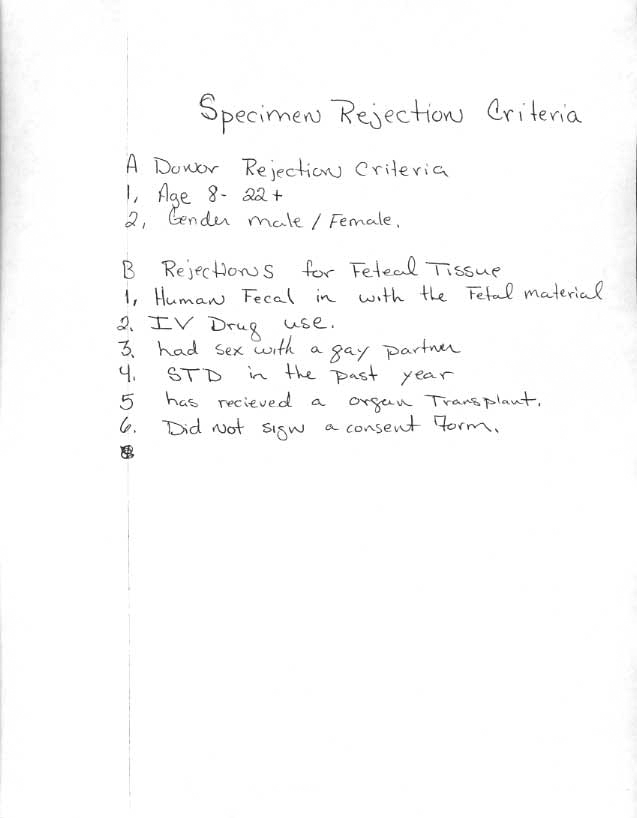

To help the reader of this report have a more complete understanding of the “mechanical” aspects of the baby parts business, we are providing documents that describe the recommended methods for procuring parts. These instructions came from Comp Health and were given to retrieval agents employed at that facility. Also included in this section are a few pages of hand-written instructions. These are notes made by Dean Alberty from oral directions he was given when he first began harvesting parts at Comp Health.

Another aspect of the baby parts business is the question of whether women are ever coerced to donate their baby’s body.

According to people we talked to during our investigation, coercion is not a problem because it is not necessary. The consent document is usually just “thrown-in” with the other papers the patient is told she must sign before the abortion can be done. In most cases, the woman never knows that she gave permission.

Beyond that, people in the baby parts business recognized long ago that even if they harvested aborted babies without the mother’s permission, the possibility of being caught is virtually zero. When a woman leaves an abortion clinic, she has no idea what happens to her dead baby and almost no incentive to find out. Furthermore, if she decided to pursue the issue it would be impossible for her to ever determine for certain whether her baby’s corpse was thrown in a dumpster, flushed down the sewer system, incinerated, carried off by a medical waste company, or sold for parts. In fact, it would be impossible for even a trained law enforcement investigator to make such a determination. The reality is, regardless of what the clinic says happened to the dead body, there is no way for an outside entity or individual to prove otherwise.

Despite that, however, some clinics do request consent.

In those cases, fetal tissue donation is inevitably sold to the patient as “something good” that can come from her decision. Although patients are not supposed to be approached about tissue donation until after they have given written consent for the abortion, we were constantly told by industry insiders that the subject is often brought up during the initial counseling session. Obviously, for women who are hesitant about going ahead with the abortion, this could be a compelling emotional inducement to proceed.

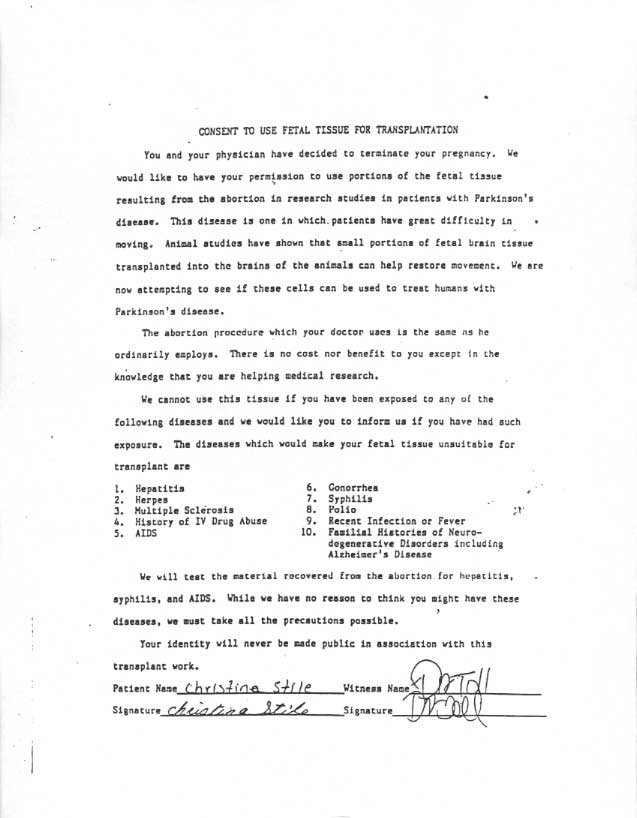

In clinics where this “something good” approach is used, it is generally reinforced with a consent document that is, in reality, little more than a subtle sales pitch designed only to secure the patient’s permission. This is evident in the consent form used at the Mayfair Women’s Center, an abortion clinic in Aurora, Colorado. During our investigation, we were not able to obtain any other consent documents but we were assured that this one is typical of those used around the country. In fact, among the people we dealt with in the baby parts business, it is almost universally accepted that the wording for these documents was actually produced by one of the wholesalers.

This particular consent form is for an 18-year-old girl named Christina Stile who had her abortion at Mayfair on June 29, 1993. Tragically, the signature on this paper turned out to be the last time this young woman ever wrote her name. The abortionist, Ron Kuseski, botched the procedure and within a few minutes Ms. Stile was in a permanent vegetative state. Since her abortion, she has required around-the-clock care and will do so for the rest of her life. We were never able to document whether her baby was chopped-up and sold for parts. Also, we were never able to determine whether Kuseski altered the procedure to obtain the parts and, if so, whether this played a role in the injuries she suffered.

Trafficker’s Reactions

Opening Lines:

Immediately after we began releasing information on the marketing of baby parts, the operator of Opening Lines, Myles Jones, closed his West Frankfort, Illinois, facility and, literally, sneaked out of town in the middle of the night. Since then, we have received several reports about Jones and his assistant, Gayla Rose, resurfacing in other states.

AGF:

In December of 1999, AGF announced it would no longer be providing baby parts. Apparently, this was in response to public exposure in the media and protests by pro-life activists at their Maryland headquarters.

We have always been aware that there are other wholesalers in the baby parts business besides AGF and Opening Lines. However, we have also learned that some researchers are now cutting out these middlemen and going directly to the abortion clinics. In these cases, the site fee and reimbursement system is often replaced with one based on bartering. Our information is that the most common scenario is for a medical school to provide free pathology reports to an abortion clinic in exchange for free baby cadavers and/or body parts.

This new bartering arrangement seems to be an attempt by the clinics and these schools to blunt any charges that they are trafficking in baby parts. However, if an abortion clinic is trading baby parts for services which it would otherwise have to pay for, and the school is trading services for baby parts it would normally have to buy, both are still in violation of those statutes which prohibit trafficking in human body parts.